Likes

1

Want to Read Shelf

1

Read Shelf

0

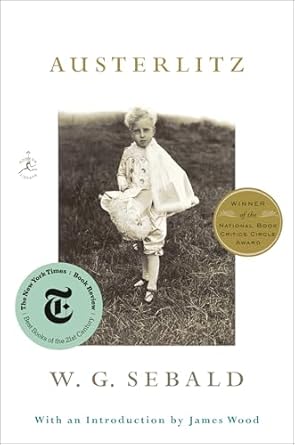

Austerlitz

W. G. Sebald

W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz is a haunting, labyrinthine meditation on memory, history, and identity, interwoven with a deeply melancholic reflection on the irretrievable loss caused by the Holocaust and the fractured nature of personal and collective remembrance. The novel unfolds through the narrative voice of an unnamed narrator, who encounters the enigmatic Jacques Austerlitz, a solitary architectural historian whose life is marked by an unconscious rupture—a break in his own past, obscured by the shadows of war and displacement. As Austerlitz reconstructs his own history, gradually uncovering that he was born in Prague and sent away on a Kindertransport to Britain before the Nazi occupation, Sebald’s prose meanders through vast networks of associations, tracing the interstices of personal trauma and the broader devastation of Europe’s twentieth-century catastrophes. The novel’s semantic complexity emerges from its hypnotic, recursive sentence structures, which mirror the inexorable circling of memory, as well as its ekphrastic descriptions of photographs, architectural spaces, and archival materials, all of which serve as spectral markers of an occluded past. Sebald’s refusal to employ conventional paragraph breaks, his use of long, meandering sentences, and the novel’s elegiac tonality create a hypnotic rhythm that immerses the reader in a state of reverie, reinforcing the themes of dislocation and the impermanence of historical consciousness. The imagery of decay—abandoned fortresses, derelict railway stations, and neglected libraries—functions as a metaphor for Europe’s eroded historical memory, and Austerlitz’s architectural observations become a means of uncovering the buried traumas encoded within physical spaces. The novel’s interplay between text and image—its incorporation of enigmatic, grainy black-and-white photographs—introduces a destabilizing effect, forcing the reader to navigate between fiction and documentary, imagination and evidence, memory and oblivion, which further complicates the novel’s epistemological concerns. Sebald’s thematic preoccupations with exile, loss, and historical absence coalesce through his exploration of how the past imprints itself upon the present, often in ways that remain incomprehensible or unutterable, as Austerlitz’s journey toward self-discovery is continually thwarted by gaps, erasures, and the limitations of language itself. The novel’s semantics are suffused with an elegiac cadence, a sense of linguistic mourning that underscores the inefficacy of words to fully encapsulate historical horror or personal suffering, as if the very act of narration is both an attempt at reclamation and a testament to the failure of such an endeavor. Memory in Austerlitz is not linear but fractured, a spectral force that emerges unpredictably, much like the protagonist’s own recollections, which surface through chance encounters, objects, and places that act as inadvertent triggers of suppressed knowledge. Sebald’s fascination with liminal spaces—train stations, borderlands, fortifications—parallels the novel’s thematic concern with displacement, as these transient, interstitial locations become the physical embodiment of exile and impermanence. Furthermore, the text’s preoccupation with archives and documentation—its engagement with history as a shifting, unstable terrain—underscores the fragility of historical records, the ease with which lives can be erased, altered, or forgotten. The specters of the Holocaust linger throughout the novel not through direct representation but through haunting absences, the unspoken, the implicit, the barely perceptible, creating a tension between what is remembered and what resists articulation. Sebald’s prose, with its recursive syntax and melancholic lyricism, mirrors the novel’s central themes of fragmentation and loss, enacting the very processes of forgetting and remembering that define Austerlitz’s existential struggle. The novel ultimately resists closure, offering no definitive resolution to its protagonist’s quest for identity, reinforcing the notion that history itself is an unstable, spectral presence, one that eludes capture even as it insists upon its persistence in the ruins and remnants left behind. Austerlitz thus becomes not only an exploration of an individual’s attempt to reconstruct his past but also a profound meditation on the nature of memory, the ethical imperative of remembrance, and the silent, inexpressible grief that lingers in the margins of history, waiting to be acknowledged yet never fully grasped.